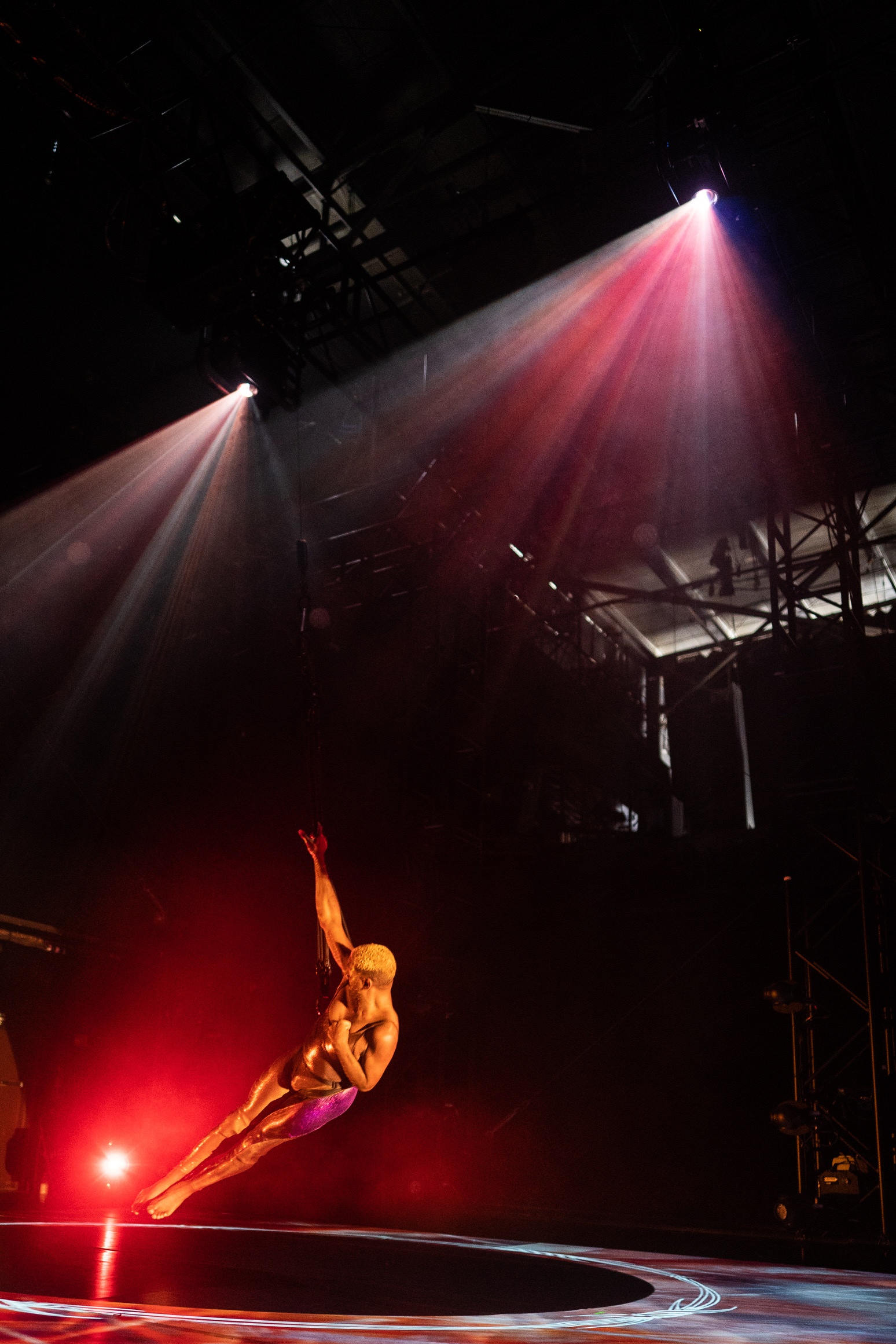

For the artists of the disability arts ensemble Kinetic Light, barbed wire is a quintessential, complicated material of US history and contemporary life, organizing movement and confinement by marking territory from farmland and construction sites to prisons and international borders. Wired, their Open Call commission opening August 25 at The Shed, explores the race, gender, and disability stories of this prickly material in an aerial performance experience of sound, light, and movement.

When Alice Sheppard founded Kinetic Light in 2016, she brought together a group of interdisciplinary disabled artists to create and perform. Along with Sheppard, Kinetic Light artists, dancers Jerron Herman and Laurel Lawson and scenographer and lighting designer Michael Maag, collaborate on works developed out of the intersecting frameworks of access, queerness, disability, dance, and race. Their approach combining art, technology, access, and design is perfectly suited to delving into the beauty, connection, and the troubled meaning of barbed wire in human infrastructure. Maag and Sheppard took time out of their August rehearsals for Wired and other projects to talk about their collaborative process, the origins of Wired in an engagement with sculpture, and what barbed wire and light can reveal to us about the world we live in.

The Shed:

With less than a month until Wired opens at The Shed, what are you working on right now?

Alice Sheppard:

For a project like this, rehearsal is endless—in part because of the technical requirements. In this show there is an intimate and necessary relationship between lighting and video projection and movement. Right now, as we put the final touches on the work, we’re focusing on making sure that when a light goes on or a video projection starts, that we [the dancers] aren’t three feet across the stage, going in the wrong direction…

Michael Maag:

And I’m watching what you’re doing in rehearsal so that I can respond appropriately because, of course, we’re creative artists and there are changes in rehearsal. From my perspective right now, the work has largely shifted from the artistic to the technical, but I’m also keeping an eye on what’s happening for any changes that will influence the visual environment.

Sheppard:

This is not the call to tell you about all the choreographic changes we made today, right? [laughs]

Maag:

No, that’s a different call. [both laugh]

The Shed:

So you’re working at a distance from each other right now?

Maag:

We’re at a distance. Alice, Jerron, and Laurel are in Brooklyn rehearsing, and I’m in Ashland, Oregon, at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival working on productions of Confederates and King John. I’m in tech for those at the moment.

Sheppard:

We were working virtually before the pandemic. That’s really a practice of disabled artists and so the demands of the pandemic were already answered by some of the ways that we were already operating and creating together. It’s not unusual for us to be in different parts of the country, digging into the same work.

The Shed:

How does an idea for a new production begin? How do you work as a collaborative group?

Sheppard:

Historically pieces have started with me architecting, framing, directing, researching, conceptualizing. But what’s fascinating is that once the process begins, we find ourselves in a very different space in terms of our roles within the group. You might think that Michael’s responsibility is to make sure there’s a light that goes on and off. In fact, Michael’s role is storytelling and the visual look of the work as a whole. As we get further into a work, I find Michael making choreographic suggestions or pushing into the story or visual look of the piece. Michael, I should let you describe what you do…

Maag:

Often the spark does start with Alice though we all bring all of our artistic and technical inspiration to the table when we get together to start riffing on an idea. I think Laurel and Jerron would say the same thing. When we are together sitting around the same dinner table, which does happen, the ideas explode. Then we start doing research, each of us as individuals, to develop the dramaturgy, to understand the subject that we’re getting into. From that research, we establish a shared vocabulary.

To take Wired as an example, we learned there are more than 2,000 different patents on barbed wire. One of these types of wire, the Allen double-stranded 4-point, inspired an embodiment and a movement. That became something that I could then take and model in my 3-D software, which then inspired a visual environment that manifested itself in projections or angles of light, or the overall shape of the stage. So we dig through the research to create a feedback loop. I come back with an idea that the others twist a little further. Ultimately, the art is knowing when to stop.

Sheppard:

You know what, Michael? I’m remembering carrying the Encyclopedia of Barbed Wire to Ashland to visit you. And sitting together in a studio pouring through the pages, and then taking it down to Atlanta to see Laurel.

The Shed:

Michael, you just mentioned your use of 3-D software, and, Alice, you’ve written that Wired began in an encounter with Melvin Edwards’s sculpture Pyramid Up and Down Pyramid (1969, refabricated 2017). What’s the relationship of sculpture to light and performance?

Maag:

Light and shadow are the essence of sculpture. Light is invisible; we never actually see it. We only see what light reflects off of. And shadow is always there first, it’s where we start, so we’re carving out of darkness with light. The lines of light that we carve can be sharp or soft, straight or curved, colorless or colorful. There are also projections, which are visual screens or moving paintings. I have an infinite palette of tools to work with in light and shadow so that I can create an environment and tell different emotional stories.

Storytelling is an important part of my process. I have to have a story to create a section of lighting to move through a piece. I use the light to tell that story to myself, and I’m conveying something that hopefully—pardon the pun—illuminates the embodiment that the dancers bring to the moment. In a way the dancers light themselves. They do their thing and in response the light comes out of me.

Sheppard:

It does feel like that watching you work, Michael.

I want to back out slightly. These questions of light, sculpture, and movement are not separate from each other. Melvin Edwards’s description of sculpture is multidisciplinary; he considers it a way of drawing a line in space in the same way that footballers draw plays in space and choreographers notate movement. These formal elements all track in his mind, and they track in my mind and body too. When I first encountered his sculpture at the Whitney Museum, I came around a corner and the first thing I wanted to do was get in the sculpture. I was leaping out of my wheelchair trying to get really close to this artwork. Immediately it occasioned a movement, a kinesthetic response. Even though we think of sculptures as not moving, in this moment it did.

The Shed:

What has surprised you in your use of light in creating Wired? Have any ideas for the next project been sparked?

Maag:

The end of any process is the beginning of the next. Some aspects of the design of Wired are a direct result of our wishes and our dreams while we were building our previous work DESCENT, which premiered in 2018. The next piece is already growing in our minds and in our conversations.

With Wired, I was amazed to learn how important barbed wire is to the history of the United States and the world. The world we live in today would not exist the way that it does without it. It changed migration patterns, the way we treat each other.

I’ve found a direct analogy between light and barbed wire. Barbed wire keeps us in or out; light is similar. You are in the light or you are out of the light, right? If you walk around New York City or Ashland, Oregon, looking for barbed wire you don’t have to go very far. It’s everywhere. It is the light that you are in. Whether farming or ranching, fencing, war, prisons, its uses are ubiquitous in our society. We live in a world that is built around having prickly things poke at us and hurt us to keep us in or out. I don’t want to live in a world like that, which goes back to what this company is really about: bringing about change so that we’re not keeping each other in or out.

Sheppard:

Barbed wire’s omnipresence has fascinated me, too. I thought I would have to invent the research, but actually the research was already present in the number of patent lawsuits and copyright debates alone, which are all about how to cause pain and prevent someone from doing something or going somewhere.

When I started telling people the piece would be about barbed wire, I started to receive stunning stories from those I was speaking to about noticing barbed wire and finding it beautiful, as well as contact stories about touching the wire, being cut, having scars, fixing, laying, or fencing with the wire. I have an archive of stories people have told me.

Maag:

In the early days, barbed wire was the only metal that ran from farm to farm. Before telegraph wires went up, it represented a certain mode of communication. One of the sections in Wired is about telecommunication, and it tracks our thinking on this part of barbed wire’s history. We’ve been thinking about the analogy of barbed wire to social media and the current environment that we live in. Social media is a prickly, dangerous environment, and a challenging one for the disabled community.

Sheppard:

It remains fascinating to me that barbed wire is in the news almost every day. It both creates the news, and sometimes it is the news. It’s significant as a material, and yet its signification is not settled. After 100 years, it’s incredible that we’re still trying to finalize its cultural significance.

In Wired, both barbed wire and light function together in a way that sets the context for interpretation. Michael’s lights and projections set the frame, such that in each moment they are both the art and the context of that moment. The framing, the shape, the space, the delineation of the environment. Michael’s work asks us to stay alive to the ongoing creation and designation of space that we find in light and barbed wire as materials.

In terms of access, we’re also asking how all the components work together all of the time, but also how each separately conveys the work. It is possible to understand the work purely in its light. That fact points to a rich and complicated design.

Maag:

And I hope you’re able to understand it without the light, too, because not all of us experience light in the same way, or at all. I love the feedback that happens when the audio describers give us their script after watching a piece. They pick up on things that I didn’t see at first.

We have a lot of discussions while we’re working on choreography about defining the space and what the space means to the dancers at a given moment. We ask ourselves: What is the floor at this moment? Why are we touching it? Are we touching it? Deep, philosophical nonsense that nobody else needs to know about. [laughs] We do have a developed process that digs deep and hopefully shows in what we’re presenting.

Performance Details

Kinetic Light’s Wired runs August 25 – 27 at 7:30 pm in The Shed’s Griffin Theater.

Running time: Running time: 1 hour 45 minutes, with one 20-minute intermission

Tickets are now sold out but an in-person wait list will be available at The Shed 15 minutes before the show starts.