In 1899, a covert anticolonial movement in Benin Kingdom, located in Southern Nigeria, dispatched a bronze-casted letter to the exiled Oba (king).1 Encoded with visual symbols, this letter detailed plans to subvert British colonial rule and restore the Benin monarchy. Despite its historical significance, there is no visual or archival documentation of the bronze-casted correspondence. The specific symbols used to convey the message remain unknown. Was it crafted in a relief style, reminiscent of the iconic Benin Bronze plaques? Or was it a three-dimensional piece? Was the letter small enough for clandestine exchanges? Or was it disguised as a religious object?

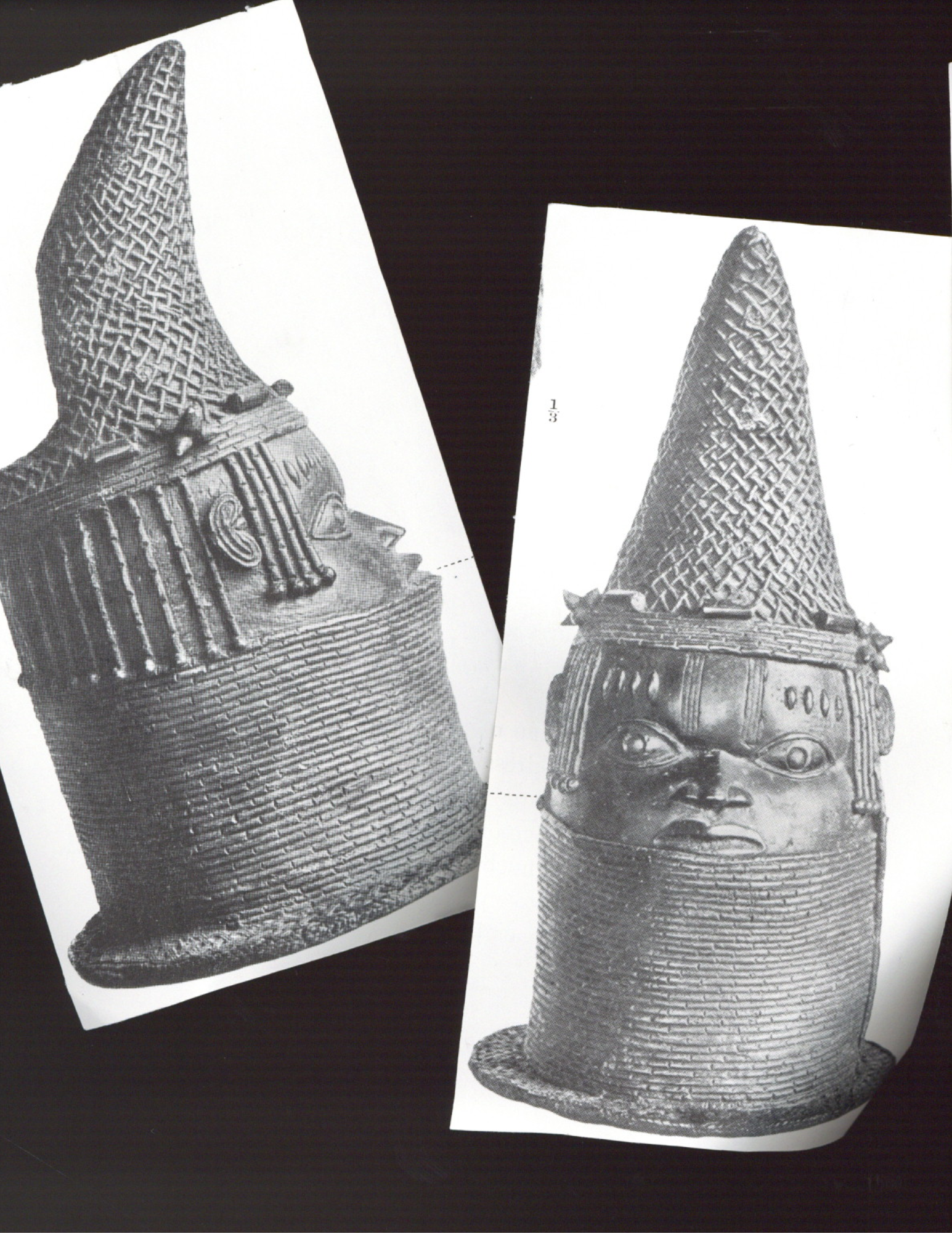

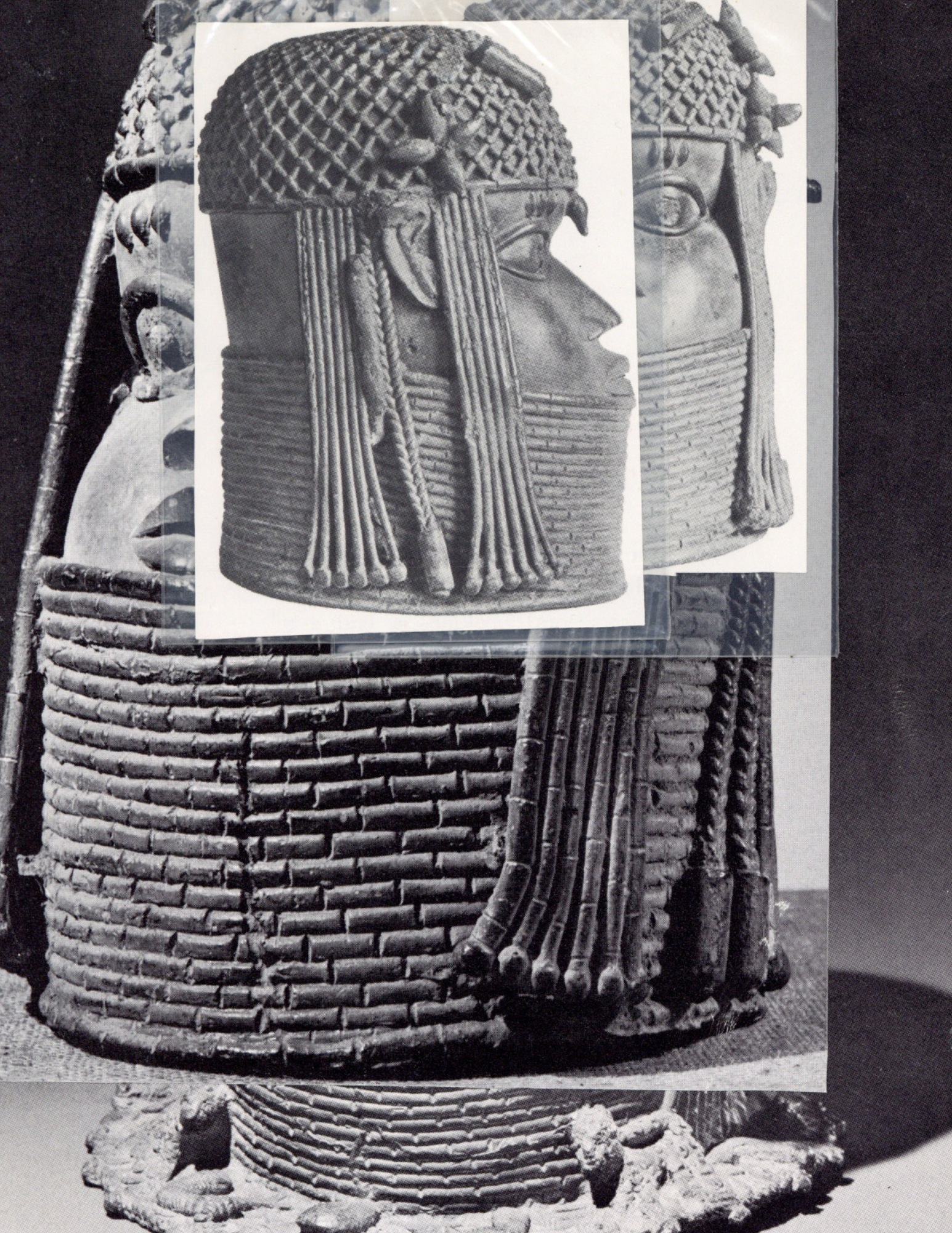

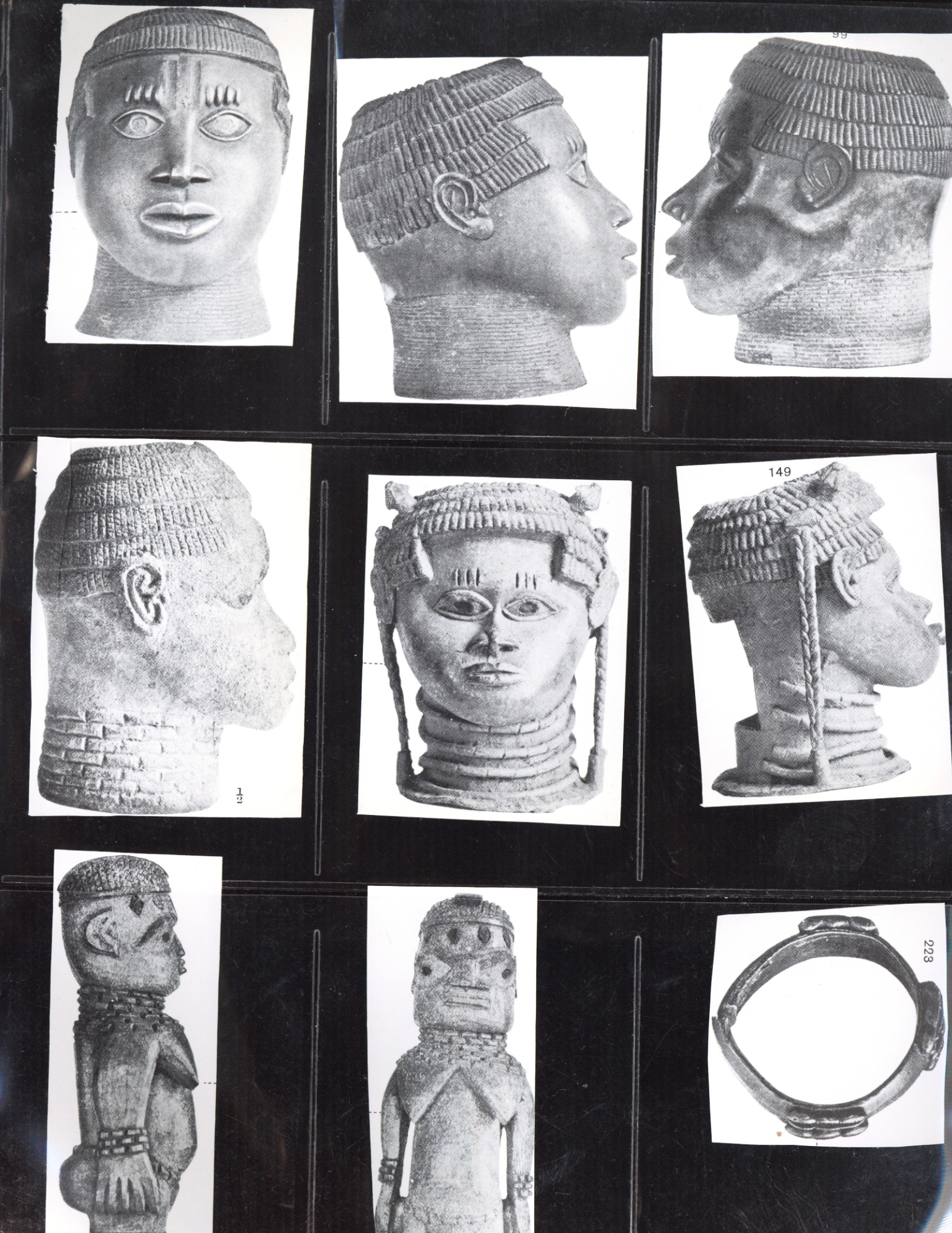

The bronze-casted letter surfaced in the aftermath of the 1897 British invasion—a devastating event that plunged Benin’s once-flourishing artistic ecosystem into a 17-year recession (1897 – 1914). This downturn began with the looting of 4,000 artifacts, collectively known as the Benin Bronzes. Following the plunder, British imperial soldiers razed the royal palace which housed artist workshops and the kingdom’s bronze reserves. Amidst the chaos, Oba Ovonramwen, the kingdom’s sole patron of the arts, was dethroned and exiled. The upheaval prompted an exodus of artists from Benin city to satellite towns, where they forsook their craft to engage in subsistence farming.2

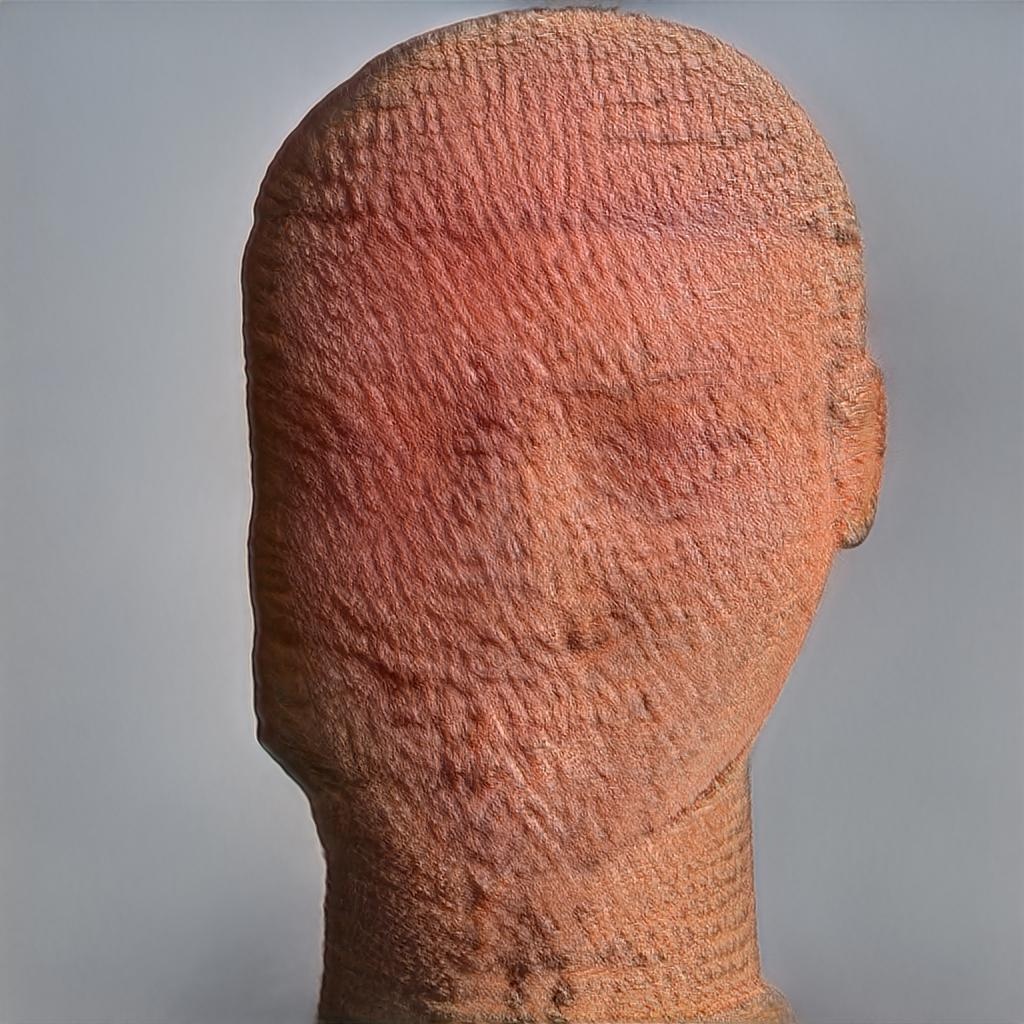

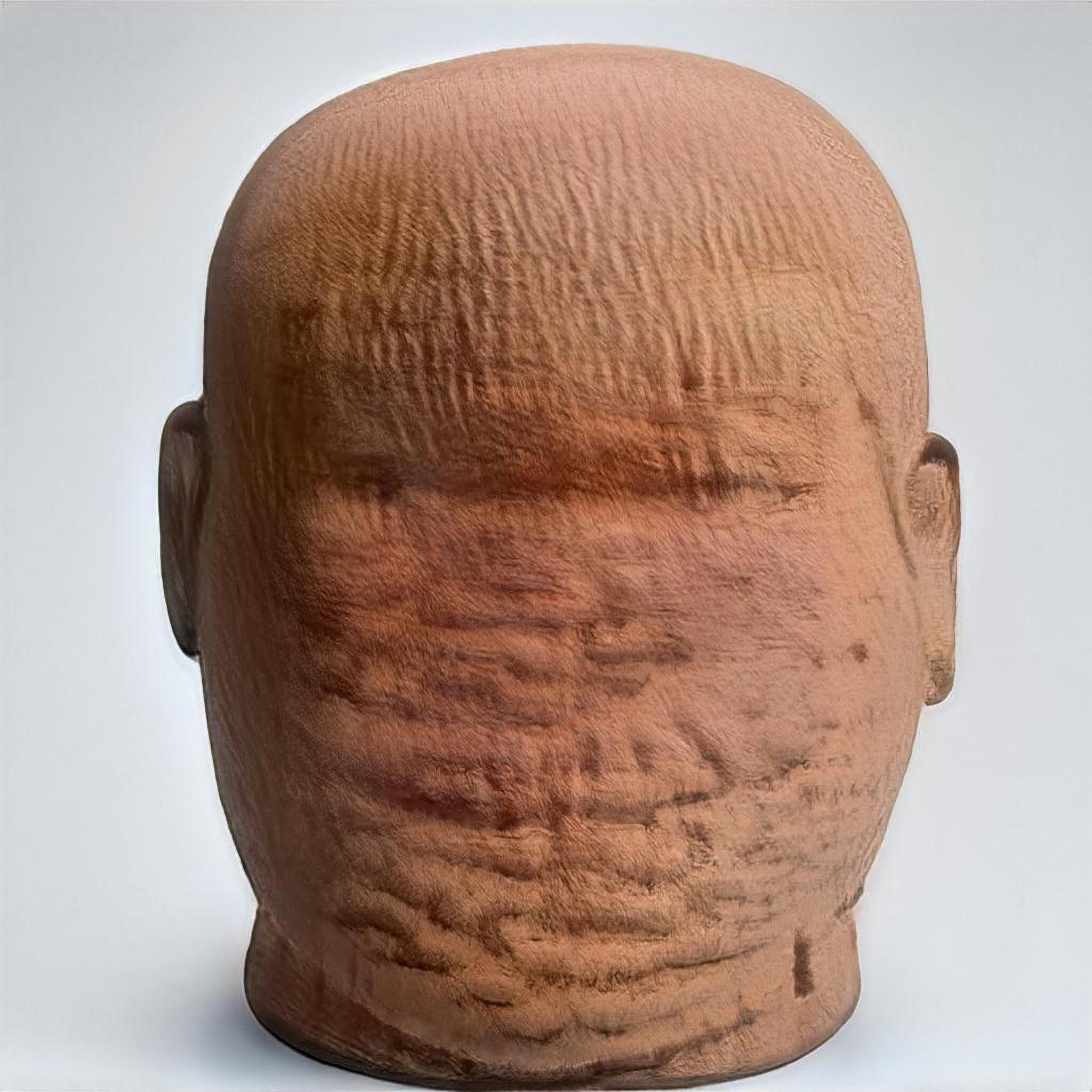

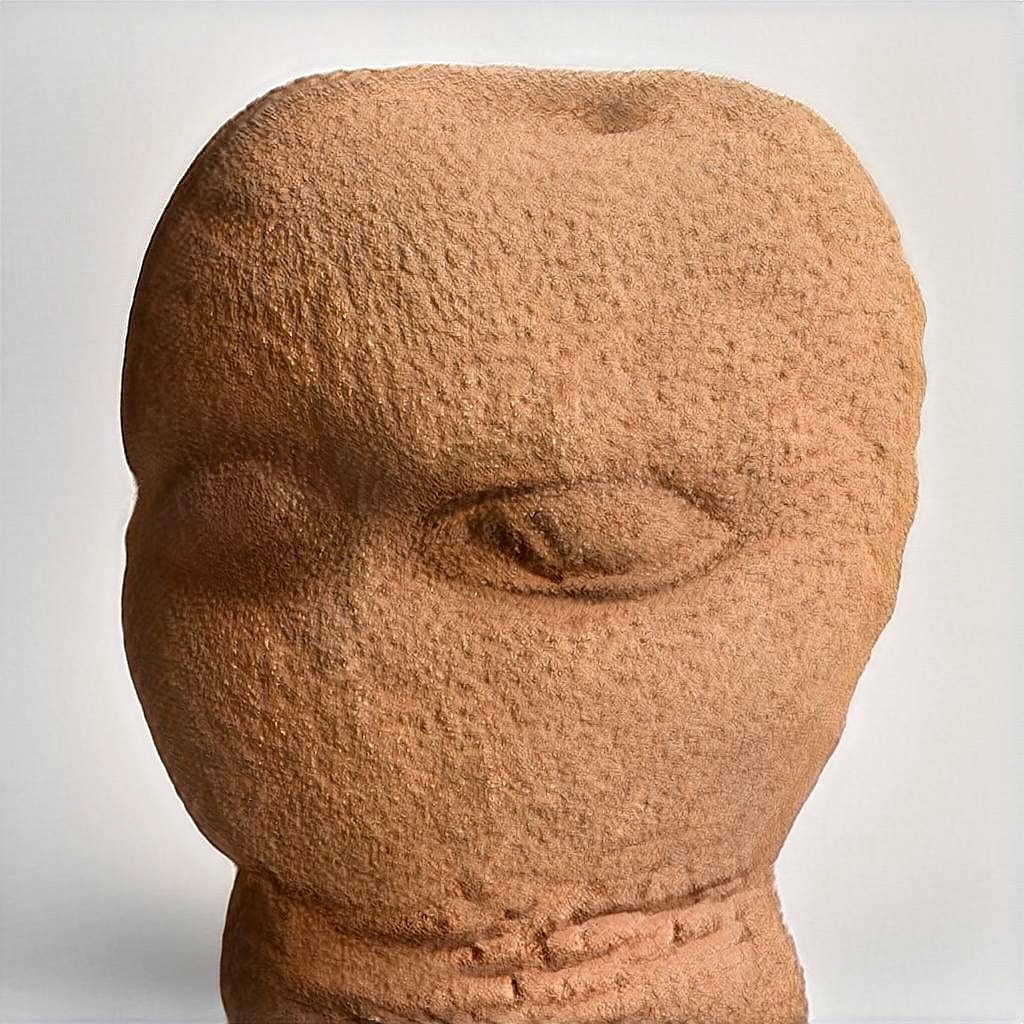

To address these lingering questions, I’ve employed styleGAN, an AI model adept at learning and generating images that possess the stylistic detail and depth requisite for this speculative study. The process begins with a critical phase known as “training.” During this phase, the StyleGAN model is exposed to a dataset of images featuring looted Benin Bronzes—all currently held in western museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This training spans two days to a week. As the model analyzes the dataset, it learns how various visual characteristics, such as shapes, textures, and patterns are interconnected. Over time, the model constructs a statistical representation that encapsulates stylistic attributes found within the dataset. Once this training is complete, the model is ready to generate plausible depictions of the undocumented artifacts.

I view the resulting images as prototypes, not intended to fill the 17-year archival void or offer closure. Instead, my hope is that they can amplify latent “histories that no history book can tell.”4

Notes

- McPhilips Nwachukwu, “Benin Bronze Casting: The Story of Power and Royalty,” accessed October 4, 2023. https://www.edoworld.net/Benin_Bronze%20casting_The_story_of_power_and_royalty.html

- E. V. Odiahi, “The Origin and Development of the Guild of Bronze Casters of Benin Kingdom up to 1914,” AFRREV IJAH: An International Journal of Arts and Humanities 6, no. 1, 2017: 176 - 87.

- B.W. Blackmun, “Continuity and Change: The Ivories of Ovonramwen and Eweka II,” African Arts 30, no. 3, 1997, 68 - 96. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3337502

- Saidiya Hartman, “Intimate History, Radical Narrative,” The Journal of African American History, 106, no. 1, 2021: 127-135.